From the delights of research-intensive body farms to the charm of the Dutch taxidermy world, here’s our weekly round up of all things death. First, a very important reminder for you to think about death.

Farewell Wishes

Are you a) Ready to think about about death? b) Mortal?

If you’ve answered yes to both, then you need to get your Farewell Wishes sorted. Head to the Farewell Wishes page to think about your send off and, most importantly, tell others! We’ve had a great response to Farewell Wishes so far – you can check out some of the reactions on our Twitter feed.

Articles on DEATH.io

Taking funeral matters into your own hands, whether by crowdfunding or not, usually means you’re going to need to get creative with a smaller budget – remember to remind yourself that cheap or DIY is still meaningful. Create your money goal with cheaper options in mind. We look at one alternative to paying for a funeral.

“BODY FARM?!” we hear you scream. Yes, that’s right – places of both research and unutterable scenes of grotesque decay. This is the kind of place you’d only find yourself if you were either dead or a microbiologist. Here we look at the vital research done on body farms, and why in the UK we’re a bit too squeamish to start creating them.

News

Death by selfie is now a public health concern. This sounds like the plot of a TV show about a near dystopian future where millennials run themselves into the ground with their wiley millennial ways. But a study this has found that the fateful quest for extreme selfies has killed up to 259 people between 2011 and 2017.

Selfie death is a brand new method of demise. Common causes of selfie death include drowning, transport accidents, fire, electrocution, as well as the more straightforward falling off a cliff backwards. It is death by natural tragedy made culpable to human

Selfie death is a brand new method of demise. Common causes of selfie death include drowning, transport accidents, fire, electrocution, as well as the more straightforward falling off a cliff backwards. It is death by natural tragedy made culpable to human

The study even suggests that selfie death is largely underreported: certain road fatalities that involve posing for selfies have been reported as Road Traffic Accidents. The true estimate might be a little higher. You can read the report here, and don’t forget to always look behind you when taking a selfie at Yosemite.

Reading

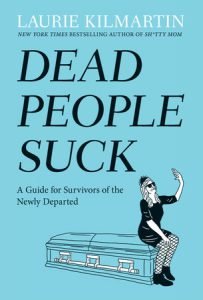

We’ve taken a look at Dead People Suck by Laurie Kilmartin, author of Sh*tty Mom and creator of the comedy series 45 Jokes About My Dead Dad. It’s an irreverent look at death, and reads as if the director of Bridesmaids wrote a book about their grief while downing shots at the local dive bar.

We’ve taken a look at Dead People Suck by Laurie Kilmartin, author of Sh*tty Mom and creator of the comedy series 45 Jokes About My Dead Dad. It’s an irreverent look at death, and reads as if the director of Bridesmaids wrote a book about their grief while downing shots at the local dive bar.

With a chapter named “Unsubscribing Your Dead Parent from Tea Party Emails,” grief isn’t for the faint-hearted or, as she shows, for those without a twisted sense of humour – you won’t find any hollow platitudes here. Kilmartin’s guide to surviving dying, death and grief is instead heavily cynical but utterly . She describes the awful numbness after someone dies in the same sentence as a filthy joke to do with peeling a banana, and the everyday becomes fraught with absurdity. Recommended, but only for those who like horrible truths served to them with a blunt stick.

Obscure

We came across an exhibit that consists solely of staged taxidermy, all arranged neatly in their preserved death scenes, called Dead Animal Tales.

A kingfisher is preserved in a near-perfect death condition, within a block of ice. Another victim to the human-world, a hedgehog is displayed with its head still stuck inside a McDonald’s McFlurry container. Unable to move, the hedgehog had finally starved to death. We can’t help thinking there’s a metaphor struggling to emerge out of that one. As well as the so-called Breakfast Bat, which fell out of a cereal box during a German family’s breakfast. It was already dead, and can be seen at the museum alongside its box.

A kingfisher is preserved in a near-perfect death condition, within a block of ice. Another victim to the human-world, a hedgehog is displayed with its head still stuck inside a McDonald’s McFlurry container. Unable to move, the hedgehog had finally starved to death. We can’t help thinking there’s a metaphor struggling to emerge out of that one. As well as the so-called Breakfast Bat, which fell out of a cereal box during a German family’s breakfast. It was already dead, and can be seen at the museum alongside its box.

The museum has in the past asked for submissions. If you’re in the mood, understand the legalities involved in posting dead animals, or simply want to rehome that pigeon you found on the M4, then look no further than the Natural History Museum in Rotterdam.

If you’ve not had enough of the strange relationship between death and animals, then look no further than the history of English literature. Many writers kept corvids as pets – it’s relevant given that the bird is the no.1 symbol of death. Truman Capote owned a raven named Lola; Lord Byron kept a crow (but, to be fair, he also kept a bear, monkeys and countless dogs). Charles Dickens, Victorian purveyor of London, kept not one but three ravens.

If you’ve not had enough of the strange relationship between death and animals, then look no further than the history of English literature. Many writers kept corvids as pets – it’s relevant given that the bird is the no.1 symbol of death. Truman Capote owned a raven named Lola; Lord Byron kept a crow (but, to be fair, he also kept a bear, monkeys and countless dogs). Charles Dickens, Victorian purveyor of London, kept not one but three ravens.

This might go some way to explain the obscure book Barnaby Rudge, which doesn’t seem to be as popular on the school syllabus as Great Expectations. The book displays an intimate knowledge of the inner workings of ravens, given that a chunk of it is written from the perspective of, yes, a raven. Dickens’ own ravens were named Grips, Grips II, and Grips III. There’s a bizarrely convoluted story behind at least one of Dickens’ ravens. You can begin your journey into the curious case of Dickens’ raven here.

Check out the Death Blog next week for more of our favourite death-related bits and pieces. In the meantime, take a look at DEATH.io to start planning ahead.